The promise of enterprise architecture is that it helps improve decision making. Typically, the role of the enterprise architect is to advise and enable other stakeholders to make better decisions. Therefore, Enterprise Architecture – more than anything else – is a social discipline, in that it demands social skills and interaction in order for practitioners to successfully engage with stakeholders and change their behavior.

Not surprisingly, enterprise architects are more effective in steering decisions when they consider that they are dealing with Humans. And Humans, as we’ve explained in our previous blog, can be irrational, naïve and impulsive. By taking these biases into consideration and making choices as easy as possible for decision makers, architects can dramatically increase the likelihood of getting their point across and ultimately help deliver better business outcomes for the organization. Here, we present some principles to get you started.

In their best-selling book Nudge (2008), Nobel prize-winner Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein introduce the concept of ‘choice architecture’, and present two types of actors: Homo Economicus and Homo Sapiens, or “Econs” and “Humans”. Traditional economic theory is based on choices made by Econs, who are perfectly rational and think like Albert Einstein, have the memory of IBM’s Summit supercomputer, and the willpower of Mahatma Gandhi. Humans, on the other hand, can forget their mother’s birthday, snack when they know they shouldn’t, and drink too much at parties. This is where Behavioral Economics branches off from traditional economics, explicitly acknowledging and accounting for the existence of human biases and their influence on everyday life and the economy.

Humans do not adhere to the rational world of traditional economics. But by understanding these human biases, we can steer (or “nudge”) choices effectively in the real world – an important ability for enterprise architects. It is not just about the decision that needs to be made, it’s about how the decision is presented to the decision-maker. In other words, enterprise architects must design the choices they present with care. They are choice architects.

Earlier in this blog series, we described two systems in decision making.

To achieve this, we should structure the design to make the options as obvious as possible and the choice as easy as possible, based on how we know the Human Type 1 decision-making system works, using the following principles (Thaler et al., 2008):

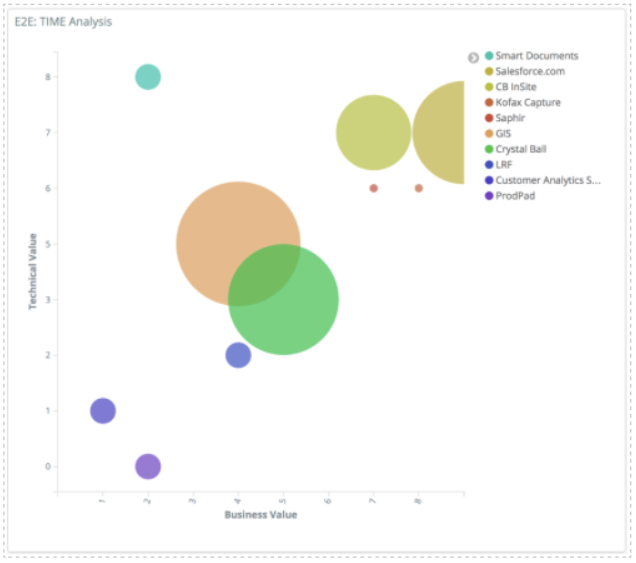

Salience of options and results can of course be manipulated, and good choice architects can take steps to direct people’s attention to incentives. Consider the rationalization of an application landscape. Applying the right filters to your decision-support visualizations helps focus attention on the ‘biggest bang for the buck.’ For example, see the BiZZdesign Horizzon visualization below.

E2E TIME analysis

We see a TIME analysis performed on an application landscape comprising over 100 applications. Since a bubble chart of 100+ applications is not easy to read – let alone make decisions on – we applied a filter to only show applications that are more expensive than $300,000. Without the clutter of the smaller applications, we can easily see which expensive applications are candidates for elimination (bottom left corner) and in which applications we should invest (top right corner). Structuring different options adequately makes every decision easier!

Next to making decisions easier, choice architects can also steer decisions when considering human bias in presenting the different options of a decision. A well-known example of human bias is loss aversion, or people’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses to getting equivalent gains: it is better to not lose $5 than to find $5. A well-known result of loss aversion is the sunk cost fallacy. After buying a non-refundable sporting event ticket, many people would feel obliged to go to the event despite not really wanting to, because doing otherwise would be wasting the ticket price. Or in a business context, “We’ve already spent so much on this SAP implementation, we just have to continue”. The recent SAP fiasco at Lidl (€500M down the drain) provides an excellent example. In bubble charts, these will be the really big bubbles on which all attention is focused. That may be another reason to filter your bubble charts in the right way.

The principles we discussed can help enterprise architects become effective choice architects and so play a big role in ensuring the organization meets its strategic goals. We believe that by accounting for human biases, they can significantly enhance management’s decision-making process and their overall performance. Therefore, we will dive into leveraging human biases in our next blog, with examples from Behavioral Economics literature. Stay tuned!