Editor’s Note:

Capabilities are fundamental to Business Architecture, making it essential to understand how to implement them effectively. To help you navigate Capability-Based Planning, we’ve created the ultimate eBook, packed with insights, strategies, and practical guidance to set you on the right path.. This blog post is an excerpt from the eBook, providing a glimpse into the valuable content you’ll find inside.

Business capabilities are stable building blocks that define what an organization does. In the first installment of this series, we gave an outline of the notion of ‘business capability’ and why it is so useful in strategy execution. But what exactly is this somewhat elusive concept, and how do you define capabilities?

As mentioned in that previous blog post, you must understand and design what an enterprise can do to fulfill its mission before diving into the organization’s structure, business processes, IT systems, and other implementation aspects. This provides the ‘big picture’ needed to deal with the challenges above: First, get away from organizational politics and technical limitations and look at the essence of what is needed.

We said that business capabilities describe an enterprise’s abilities, i.e., what it can do, independent from implementation. Of course, what it can do includes what it does today, but it also describes its potential. This makes it especially relevant in strategic discussions.

The concept was introduced mainly in the enterprise and business architecture defense domains. To quote from the NATO Architecture Framework: “A capability is the ability to achieve a desired effect under specified standards and conditions. […] In NAF, the term is reserved for specifying an ability to achieve an outcome. In that sense, it is dispositional – i.e. resources may possess a Capability even if they have never manifested that capability.”

Importantly, the concept of capability is cross-functional and cross-organizational. Capabilities are not tied to specific organizational departments, functions, or roles. Rather, what gives you a capability is the combination of various people, processes, technology, information, and other resources from across the entire enterprise.

In identifying capabilities, you want to ensure they are not bound to any specific implementation. For instance, ask yourself if a business capability would change if you split up a department or implement a new system involved in delivering that capability. If it would, then probably you didn’t identify a true capability.

This abstraction from implementation is also what makes the concept sometimes a bit difficult to understand and communicate. Most people are used to reason regarding organization structure, span of control, systems they own, business processes they manage or execute, et cetera. For instance, showing a capability map to managers often leads them to search out ‘their’ bit, where they think they are responsible because it resembles, e.g., their department. This is, of course, a misconception, but it is not always easy to overcome this instinctive reaction.

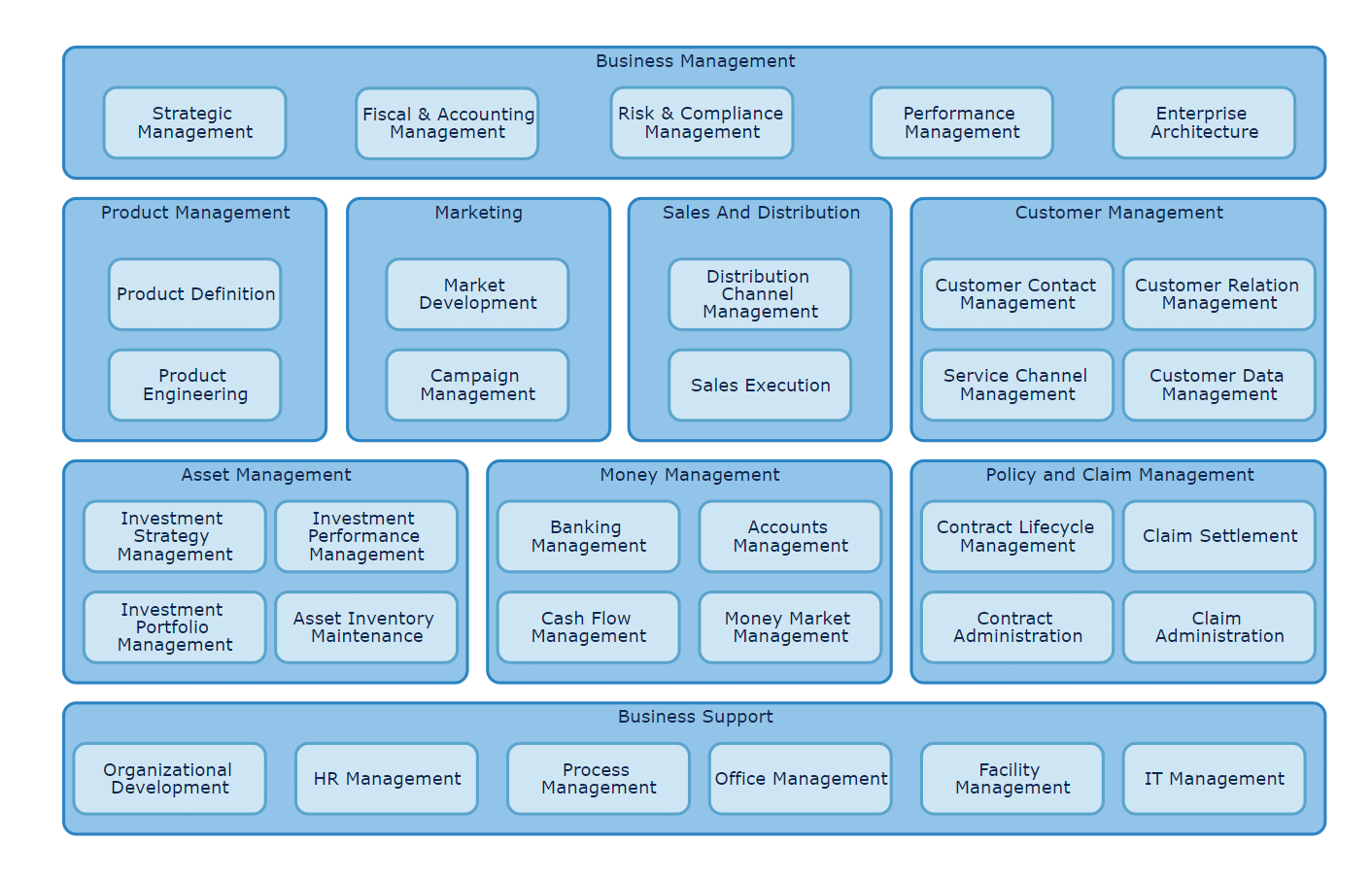

A simplified Business Capability Map of an insurance company (inspired by the Panorama 360 reference model)

Most important in defining business capabilities is, therefore, that they are named and defined in business terms by subject matter experts (often called ‘the business’ by IT people, but that is a dangerous catch-all term that we’d rather avoid). For any capability, it should be crystal clear what it does for the business. We often see capability maps that were dreamed up by IT architects without sufficient business input, using technical terms and system-level functionalities rather than true business capabilities, focused on producing some data rather than delivering real business outcomes, etc.

It helps to use a naming scheme that differentiates capabilities from other concepts, such as business processes and value streams. Where a process or value stream defines the ‘business in motion’, sequencing activities to create a dynamic perspective on business behavior, capabilities define the potential behavior of an enterprise, the ‘business at rest’, and its abilities. Processes and value streams are often named with a verb-noun scheme, e.g. ‘Adjudicate Insurance Claim’. Verbs are best avoided in capability names to avoid confusion and stress the ‘business at rest’ perspective. Such a naming scheme also helps identify capabilities. If you are tempted to name a capability like a business process, are you sure you found one?

One approach, advocated by the BIZBOK® Guide, is to identify every capability based on a specific business object and name it with a ‘business object – action’ naming convention. According to the BIZBOK, this action must not be expressed with a verb; even gerunds like Engineering, Marketing, and Accounting are explicitly forbidden: “Mapping teams should avoid using gerunds as the basis for capability names as they are not business objects and are only nouns in the nominal sense”. But their examples don’t even adhere to this commandment… Moreover, this approach focuses on information/data rather than on the true abilities of the business.

Rather than only allowing business objects as the basis for decomposing and discriminating between capabilities, we favor using the classical notions of coupling and cohesion. Pick those business-relevant criteria that create the highest internal cohesion and the lowest external coupling of capabilities. This gives you self-contained capabilities that are relatively independent and can function as true business components. Business objects are certainly one way of clustering the abilities of an enterprise but are by no means the only criterion. Markets, regions, regulatory compliance regimes, the pace of change, social relations, and various other aspects can factor into the identification and decomposition of capabilities.

Of course, you want to avoid implementation details and stay focused on the essence, but this is a gradual distinction, not something absolute. As architects, we tend to be good at generalizing and abstracting, but we must be careful. No enterprise exists without real people performing concrete activities in the context of a social fabric. If you abstract too much from that, you will surely lose your business audience.

So don’t be distracted by rigid or abstract identification or naming schemes. By far, the most important is that the name of a capability is widely recognized, and its definition is understood by all stakeholders involved as something the enterprise is able to do. Consistency and abstraction from implementation detail are important and useful, but not if they come at the cost of business understanding.

These general guidelines will help you identify your business capabilities:

Involve business experts right from the start and create a cross-disciplinary capability mapping team. Don’t let the architects define the capabilities in isolation, only asking business experts for a review afterward. Use capability reference models from industry forums as inspiration and a starting point for your work. They can also help you identify your differentiating capabilities by comparing them to the industry standard. Then, ensure your capabilities are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive: there should be no overlaps or gaps between them. Don’t be constrained by formal identification and naming schemes that don’t match business terms and understanding.

If you want further help with your Business Architecture or Capability-based planning, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Managing Consultant & Chief Technology Evangelist at Bizzdesign

Marc contributes to Bizzdesign’s vision, market development, consulting, and coaching on digital business design and enterprise architecture. He also spread the word about the Open Group’s ArchiMate® standard for enterprise architecture modeling, which he has been managing the development of. His expertise and interests range from enterprise and IT architecture to business process management.

Pre-Sales Consultant at Bizzdesign

Sven has experience in Enterprise Architecture, Business Process Modelling, and other business engineering disciplines. He has worked with various international organizations on use cases, including Capability-based Planning, Risk and Security, and IT architecture, in various projects. He has extensive knowledge of structured methods and tools, including ArchiMate, BPMN, TOGAF, etc.