As business digitization has accelerated, and every business project is an IT project, IT is under pressure to enable and support business transformation.

By defining what the organization does, business capabilities are a key concept that allows business and IT teams to speak the same language.

Business capability definition

A Business capability is defined as a representation of an organization's needs.

Business capabilities represent an organization's needs and what it does and can do. They depict the core functions of the business and break down the industry into building blocks, which are laid out in a business capability diagram called business capability maps. If needed, they can be broken down into sub-capabilities.

Their regular assessment will help enterprise or business architects identify and prioritize the corresponding IT initiatives with business needs.

Of course, since they depict an organization, business capabilities are not static and evolve; some might even become irrelevant and be replaced or consolidated by another capability. Business capabilities assessment can be based on various parameters, including efficiency, priority, and complexity.

What is a business capability example?

Take a car rental company, for example. An excellent example of business capability might be an "online booking" capability. This competence is supported by one or multiple applications, like the car rental mobile app.

Another example would be a "mortgage loan" capability for a bank supported by an in-house application that computes loans.

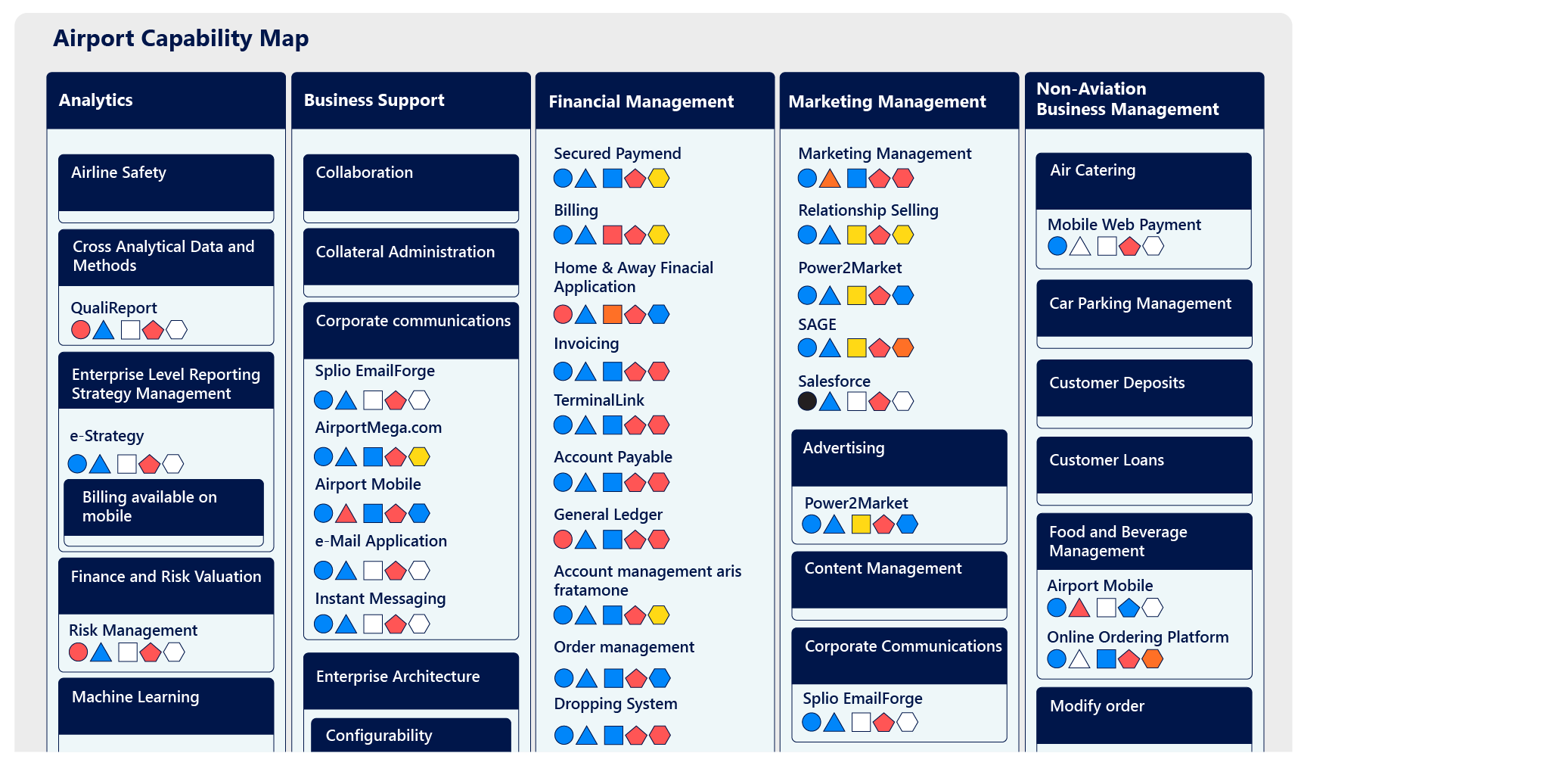

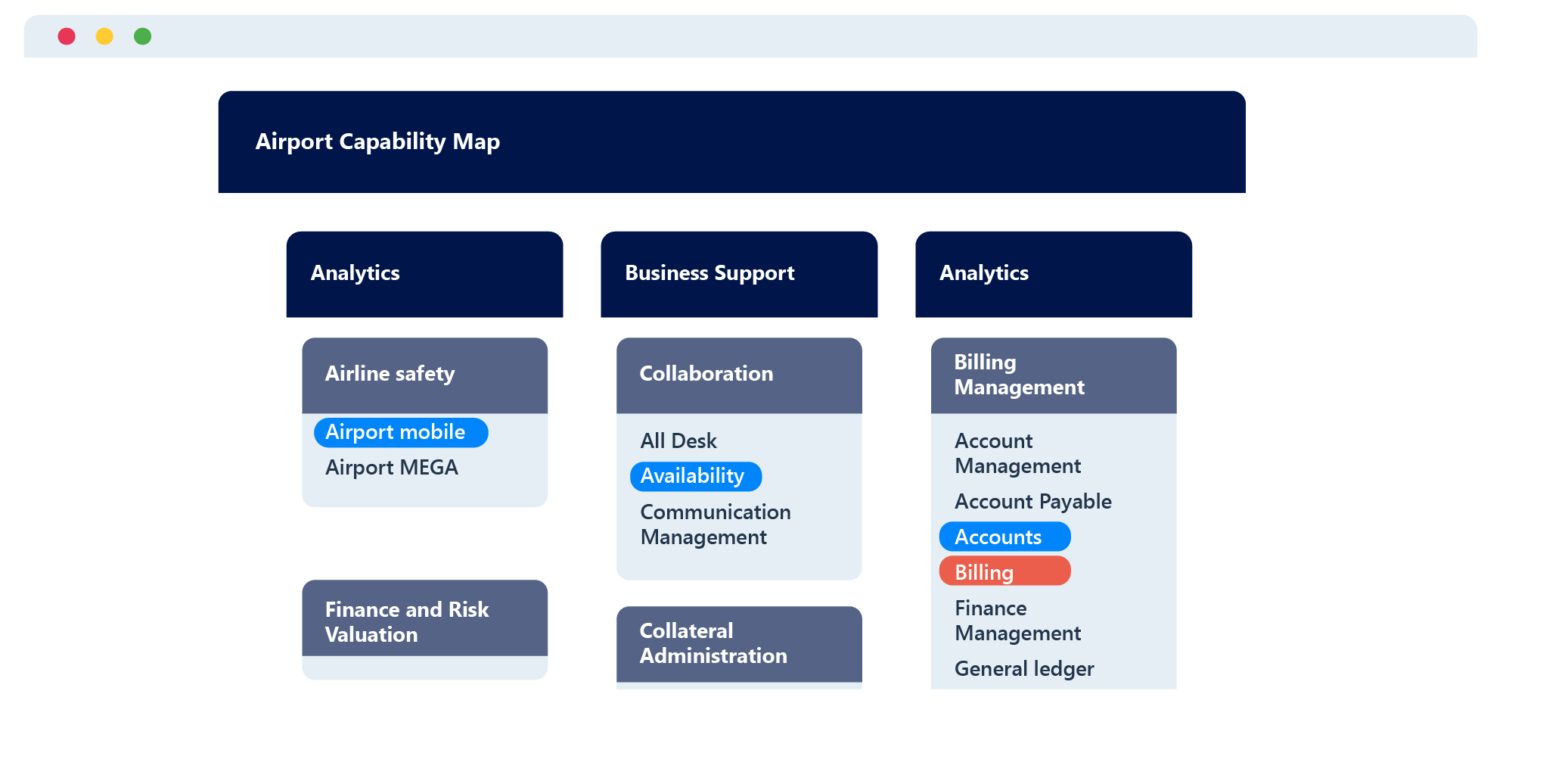

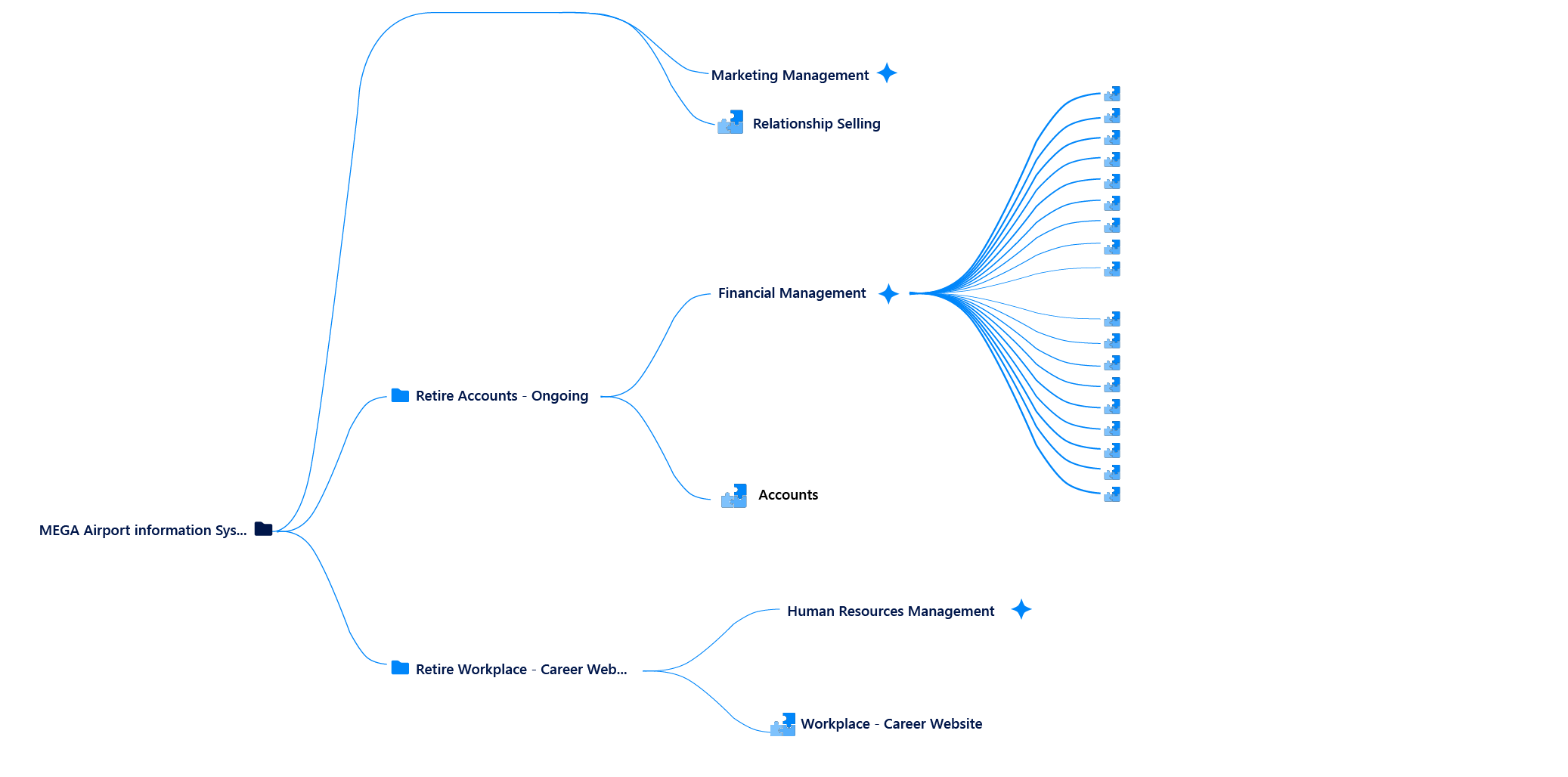

The example below shows the capability map of an airport, including applications. Each application has been assessed using color-coded icons to understand better how applications support business capabilities.

Business capability map with applications

Business capability mapping helps IT leaders shape the IT architecture to meet business needs.

Business capabilities are an essential concept that enables enterprise architects to link IT operations to the business.

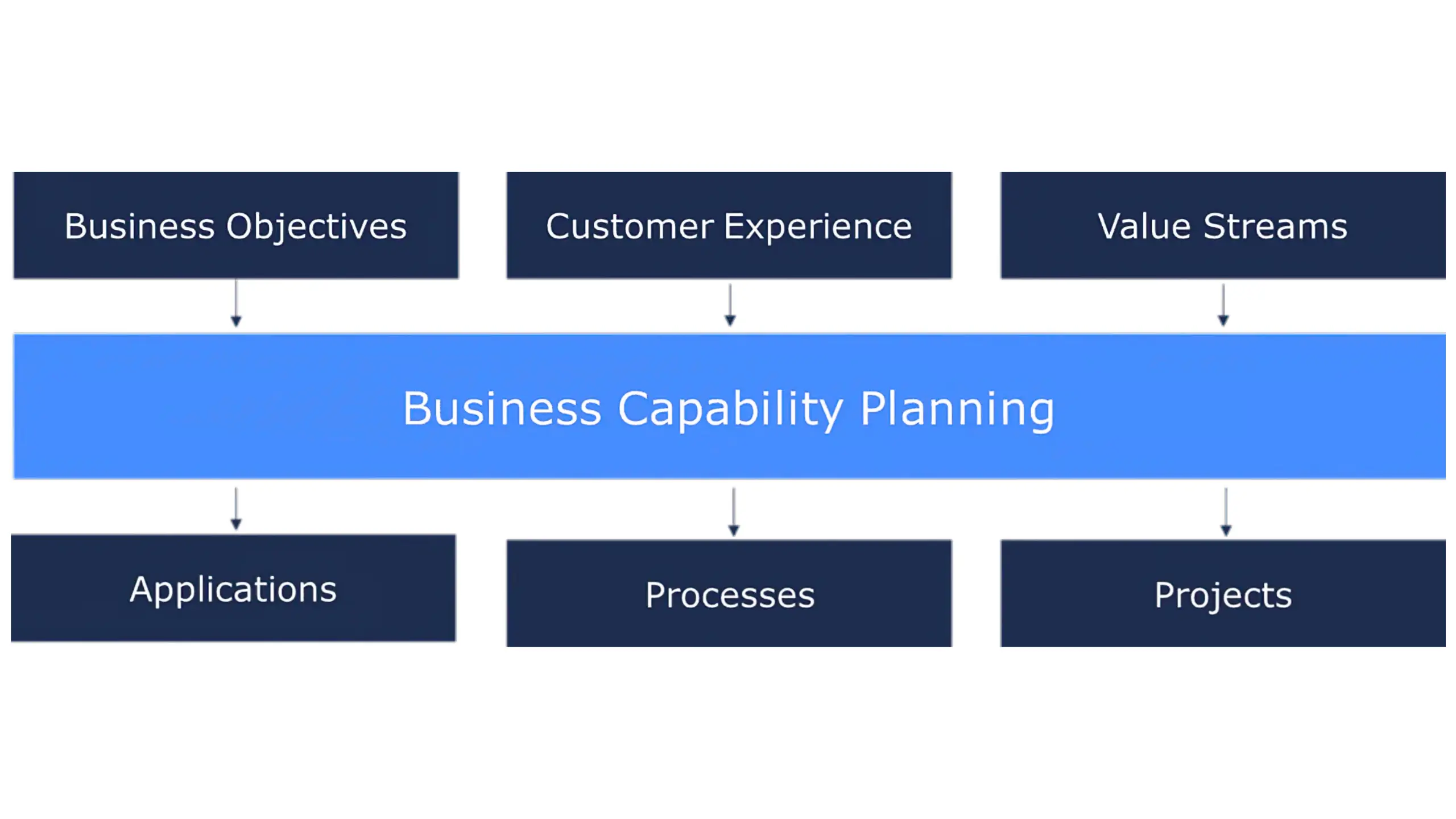

Through business capability planning, organizations can develop strategic plans that incorporate IT investments and prioritize projects.

Business Capability mapping allows companies to see what is done to reach their objectives.

To help shape the map of an organization, there is a list of concepts that "business people" connect to:

Business objectives

From the business side, capabilities connect objectives as defined by the business. By doing so, enterprise architects ensure that the company’s goals are well supported by capabilities and reciprocally that a business capability is not unreliable to the organization's needs.

Customer Experience

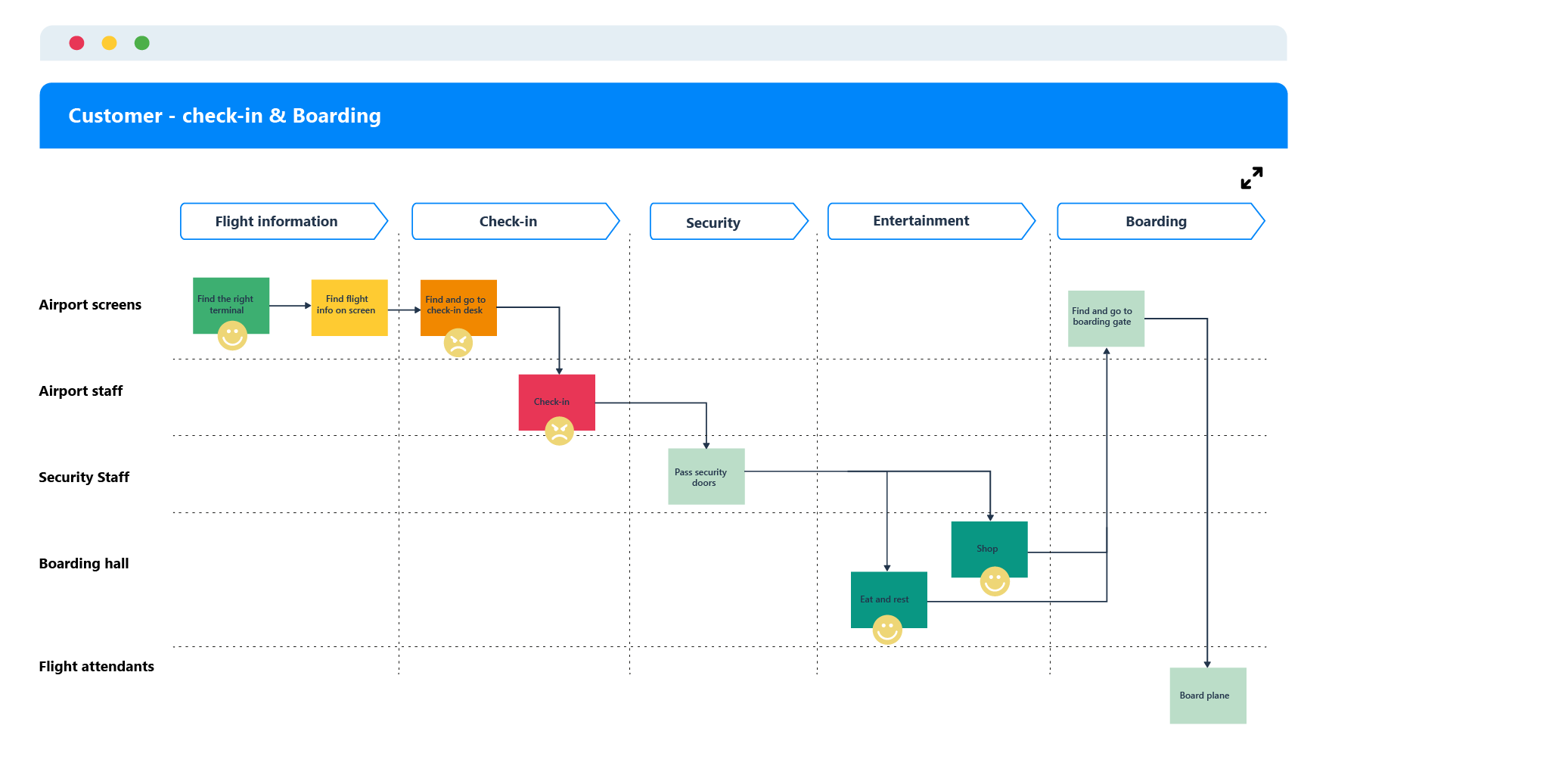

One can identify the business capabilities necessary to support the desired customer experience. Customer journey maps describe the customer experience, designing the buying cycle (research, evaluate, purchase), and the various channels available to customers, such as a company website, a mobile app, or a store.

During their journey, customers follow various touchpoints to interact with the organization.

Each touchpoint is linked to business capabilities, providing an outside-in perspective on the capabilities needed to support the customer experience.

Map customer experience in customer journey maps

Value Streams

In today’s world, especially in Agile environments, a customer-centric approach is critical to ensuring that released products deliver value and match customers' needs.

By describing the stages needed to deliver value to customers, value streams translate to IT customers' needs thanks to business capabilities.

Each stage is enabled by business capabilities so that enterprise architects can identify the required capabilities and the missing ones and plan the related IT projects.

Value stream with supporting business capabilities

To map an organization, here is a list of concepts that the "IT side" can link to business capabilities:

Applications

As we mentioned previously in our examples, business capabilities are supported by one or multiple applications.

The link between applications and business capabilities enables enterprise architects to understand the business value of applications and whether an application supports a critical capability.

Projects

Organizations must build the corresponding strategic projects and link them to business capabilities to transform or create new business capabilities.

By doing so, enterprise architects understand how projects impact business capabilities and their related applications.

Business capabilities, along with projects displayed in a business capability map

Business Processes

Finally, the organizational view with business process mapping brings the perspective on the different organizational tasks people must perform to support business capabilities.

The importance of business capabilities and business capability mapping

The ability of a business to achieve its objectives depends on its capabilities. Business capability mapping is essential to identify the capabilities required to achieve specific business objectives and to track progress over time. This helps businesses focus on the right things, invest in the right areas, and make better resource allocation decisions.

Strategic planning

Business capabilities are the foundation for strategic planning. An organization's strategic plan provides long-term visibility on a company's direction and includes action plans and resources to achieve these goals.

By associating strategy with capabilities, an enterprise architect can view the impact of business projects on their application and the IT landscape.

It will help them plan future architecture to support these business capabilities.

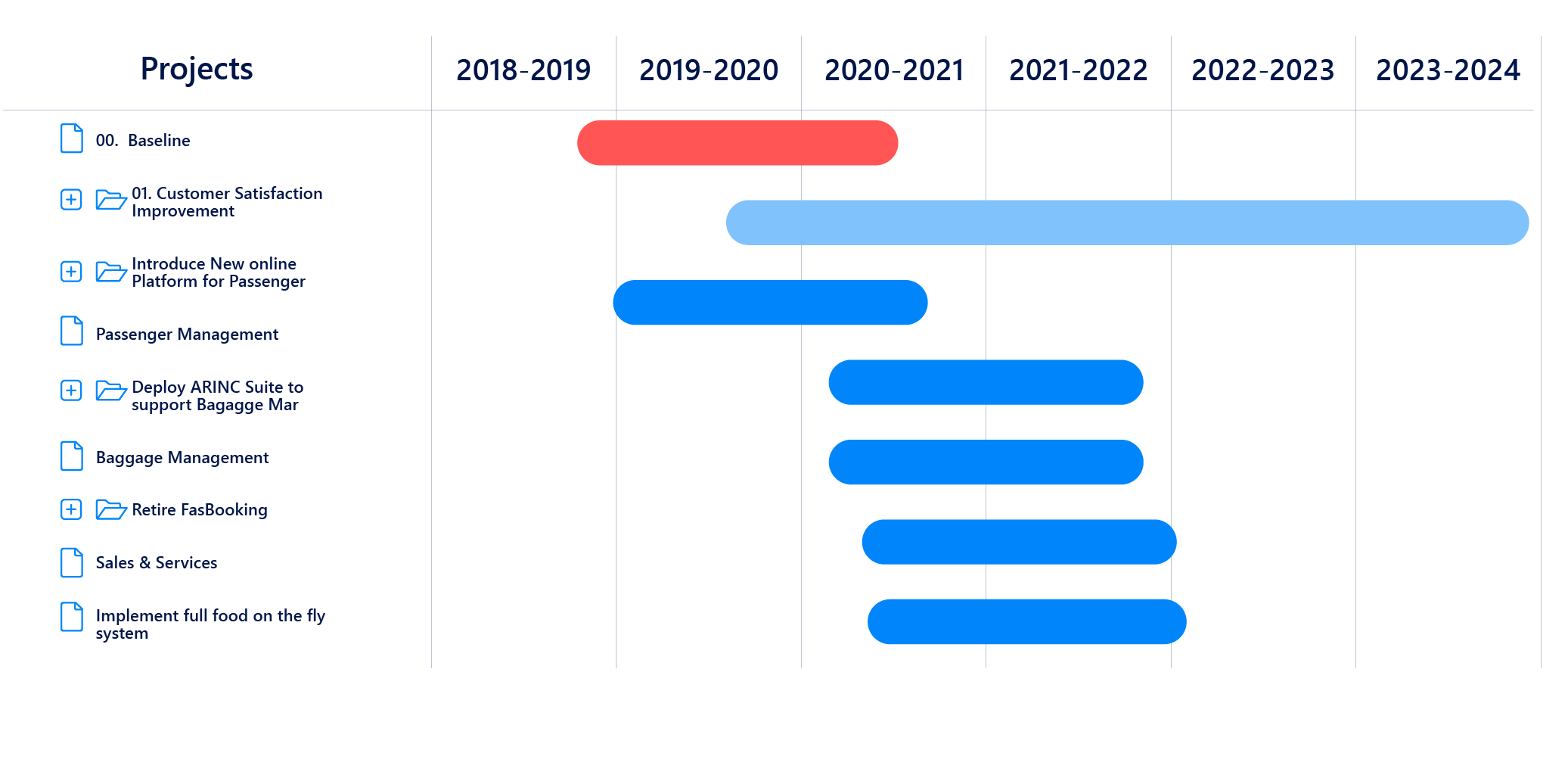

Strategic roadmap with supporting business capabilities

Customer experience in Agile developments.

Agile enterprises are organized around the customer. Even though product owners translate business requirements into user stories and software developments, they don't necessarily have the complete picture of the value delivered to the customer or the customer experience. Using value streams, enterprise architects can formalize the delivered value.

They also use customer journey maps to describe the desired customer experience. Enterprise architects plan the required business capabilities by connecting touchpoints and stages of the value streams to business capabilities. Most importantly, they can link these business capabilities to Epics and user stories so software developments are directly tied to customer experience!

Application Rationalization

Organizations have often accumulated many applications and other IT assets due to company growth or past mergers and acquisitions.

Many IT organizations fail to rationalize their application portfolio because they only have a cost perspective.

Indeed, organizations won't eliminate a business-critical application simply because it costs too much!

By linking applications to business capabilities, IT organizations can see how an application supports the business, whether it supports a critical or minor capability.

Using business capabilities also helps identify redundant applications, especially in the case of mergers and acquisitions, where the new company gains applications from the acquired company.

Technology Risk Management

In EA repositories, underlying technology components supporting applications, such as databases or software frameworks, are linked to applications linked to business capabilities and objectives.

By monitoring the end-of-life of these technology components, enterprise architects can easily understand the impact of an obsolete technology component on strategic goals.

This is also the case for an application that would use a technology that has been prohibited, as set by the company policy.

Reciprocally, enterprise architects can monitor critical business capabilities and determine if they are not being put at risk due to obsolete or prohibited technology.

Benefits of business capabilities

There are many benefits to having well-defined business capabilities. The main advantages are listed below.

Increased visibility of the business value of an IT asset

Capabilities are a great way to organize IT assets from a business standpoint. CMDBs are a critical component when managing IT assets, but they are often difficult to maintain and do not provide visibility into the business value of IT assets.

Business capabilities give an immediate understanding of the value for the business by linking IT assets to capabilities.

They enable IT departments to focus on critical assets. It is also a communication tool that offers a common language between business and IT.

Reduce IT Costs

By mapping applications to business capabilities, redundancies are more accessible to analyze and reduce costs. If two applications support the same business capability, they will likely provide the same functionalities or functional overlaps.

Adding other information, such as application cost, end-of-life, or technology obsolescence, also helps improve decision-making to remove or modernize an application.

Greater flexibility

IT departments are often swamped with existing projects or assets when managing IT projects. Don’t they see how new projects or applications fit into their existing IT systems? How will the new project impact the IT landscape? Is it redundant with another project or application? Thanks to business capabilities, IT departments increase their ability to embrace new projects by streamlining the IT landscape.

They can also focus their resources on projects critical to the business and work on what matters the most.

Improved IT investments

Business capabilities are crucial to linking strategy to execution. Business capabilities are planned in time, with strategic objectives forming the strategic roadmap.

Based on this roadmap, IT leaders determine the related IT projects, the applications, and the impacted architecture.

By aligning projects with business needs, IT departments ensure that resources are spent on suitable projects and that investments are better planned through greater visibility into upcoming projects.

It is also easier to reprioritize projects as strategic objectives change, especially in agile environments.

How do you map business capabilities?

Business capabilities link business needs to IT assets so that IT assets genuinely support the business. Additionally, business-capability planning helps enterprise architects map strategic plans and ensure that projects are aligned with business objectives.

To make sure capability maps are named and defined in business terms. Here are our guidelines for doing so:

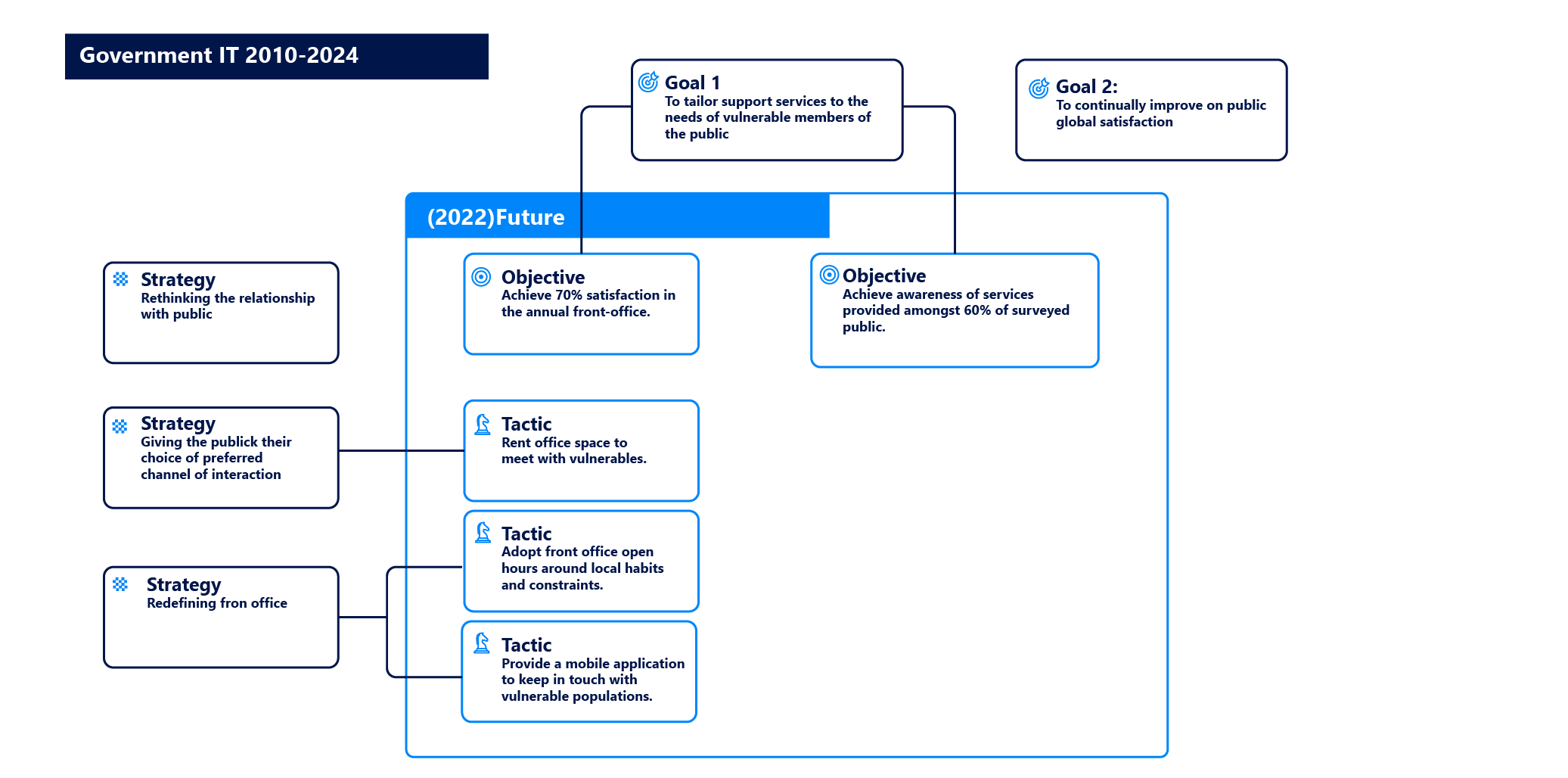

1 - Understand your organization’s strategic goals

Understanding where your organization is heading and the strategic goals defined by the executive team is crucial.

Define the mission, vision, strategies, tactics, objectives, and goals using the business motivation model to help you with this task.

Enterprise architects must work closely with the business to get insights into the organization's strategy and ensure that the business's capabilities are comprehensive.

Map out business strategy, including tactics, objectives, goals, mission, and vision

2 - Break down the business into building blocks

Meet with business leaders to understand the relevant level of detail that fits your organization’s needs and then break down capabilities into sub-business capabilities.

Note that business capability templates are available to speed up this step. They are either generic or industry-specific.

Standards bodies such as BIAN for the banking sector or the Business Architecture Guild provide generic or industry-specific templates. These business capability frameworks help accelerate business capability modeling.

Review your findings with business leaders and adjust if necessary. Establish a process for regularly reviewing business capability mapping.

3 - Link business capabilities to applications and impact analysis

In this step, enterprise architects will link the business and IT by connecting applications to business capabilities and performing a business capability analysis.

Since technology components are also tied to applications in the EA repository, you can quickly impact analysis from a technology component up to business objectives.

Business capability maps view applications and business capabilities. By using indicators on applications and business capabilities, such as application lifecycle and business criticality, you can make better decisions about the evolution of the application portfolio.

Impact analyses on projects, business capabilities, and applications

4 - Integrate the customer perspective

To plan initiatives that focus on customer needs, it is essential to connect business capabilities to the customer’s experience.

Work with epic owners or business leaders to create value streams that depict the value delivered to customers.

Work with marketing and product teams on customer journey maps to design optimal customer journeys. Identify the related business capabilities required to fulfill customer needs.

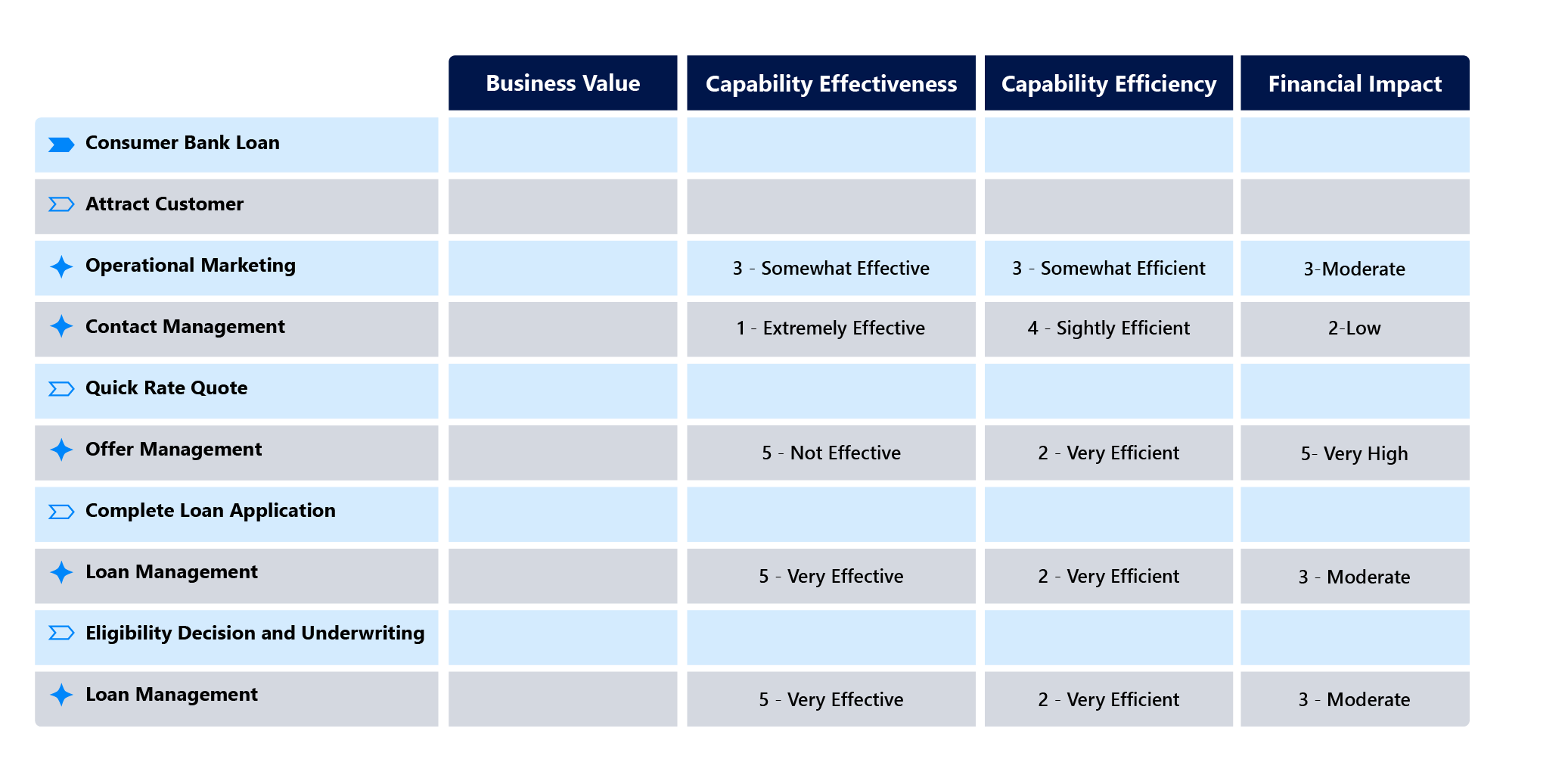

5 - Prioritize and assess business capabilities to plan project

Assess business capabilities based on priority, complexity, and efficiency to prioritize and plan business capabilities. Identify the related projects to create or transform business capabilities.

The identified projects are then planned and put into a strategic roadmap. It's important to share the strategic roadmap with your organization to review the strategic roadmap.

Assess business capabilities on various criteria.

Summary

With the help of business capabilities and Business capability maps, enterprise architects can act as strategic advisors to the business by explaining what can or cannot be done from an IT perspective.

Business capability planning will also help CIOs communicate how IT value will be delivered to the business.

FAQs

In business, a capability is defined as a combination of skills, knowledge, experience, and resources that allow an organization to perform a particular task or set of tasks. A capability can be considered an organization's "secret sauce" - the unique combination of capabilities that gives it the ability to succeed at something others cannot. Capabilities are often described in terms of processes or functions; for example, a manufacturing organization might be capable of designing and producing products. However, it is important to remember that a capability is more than just a process or function - it is the combination of skills, knowledge, experience, and resources that allow an organization to perform that process or function in a way that is unique and successful.

Business capability planning is the process of identifying, documenting, and tracking the capabilities of an organization. This includes developing new products or services, entering new markets, responding to customer needs, or taking advantage of new technology. Business capability planning aims to ensure that the organization has the right mix of capabilities to achieve its strategic objectives.

A business capability heat map is a visual tool that helps organizations understand the relationships between their capabilities and other factors, such as business goals, processes, and organizational structures. The heat map allows organizations to identify high or low-performance areas and decide where to focus their resources.

The Togaf IT business capability map is a tool used to help organizations understand and manage their IT capabilities. It provides a common language for discussing and analyzing IT capabilities and can be used to identify gaps and areas for improvement. The Togaf map is based on the Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF), a framework for enterprise architecture.

To map business capabilities, you need first to identify the different areas or functions of the business. Once these are identified, you can start mapping out how they work together and what dependencies are between them. This can be done using various methods, such as process mapping or creating a value stream map.