The benefits of application portfolio management are tremendous! This article will explain why application portfolio management tools are necessary and how they can give businesses a competitive edge.

IT departments are confronted with an increasing number of applications to manage. They often need more visibility into these applications, especially how they support the business. Companies can gain an edge in their industry by understanding and utilizing portfolio management's advantages.

APM provides organizations with organizations' inventory applications and assesses their technical and business value so that organizations can determine which ones to keep, modernize, or eliminate. IT departments use a proven methodology to reorganize their IT systems successfully.

Portfolio management will benefit your business organization. Although managing a business's applications is complex, the benefits are undeniable.

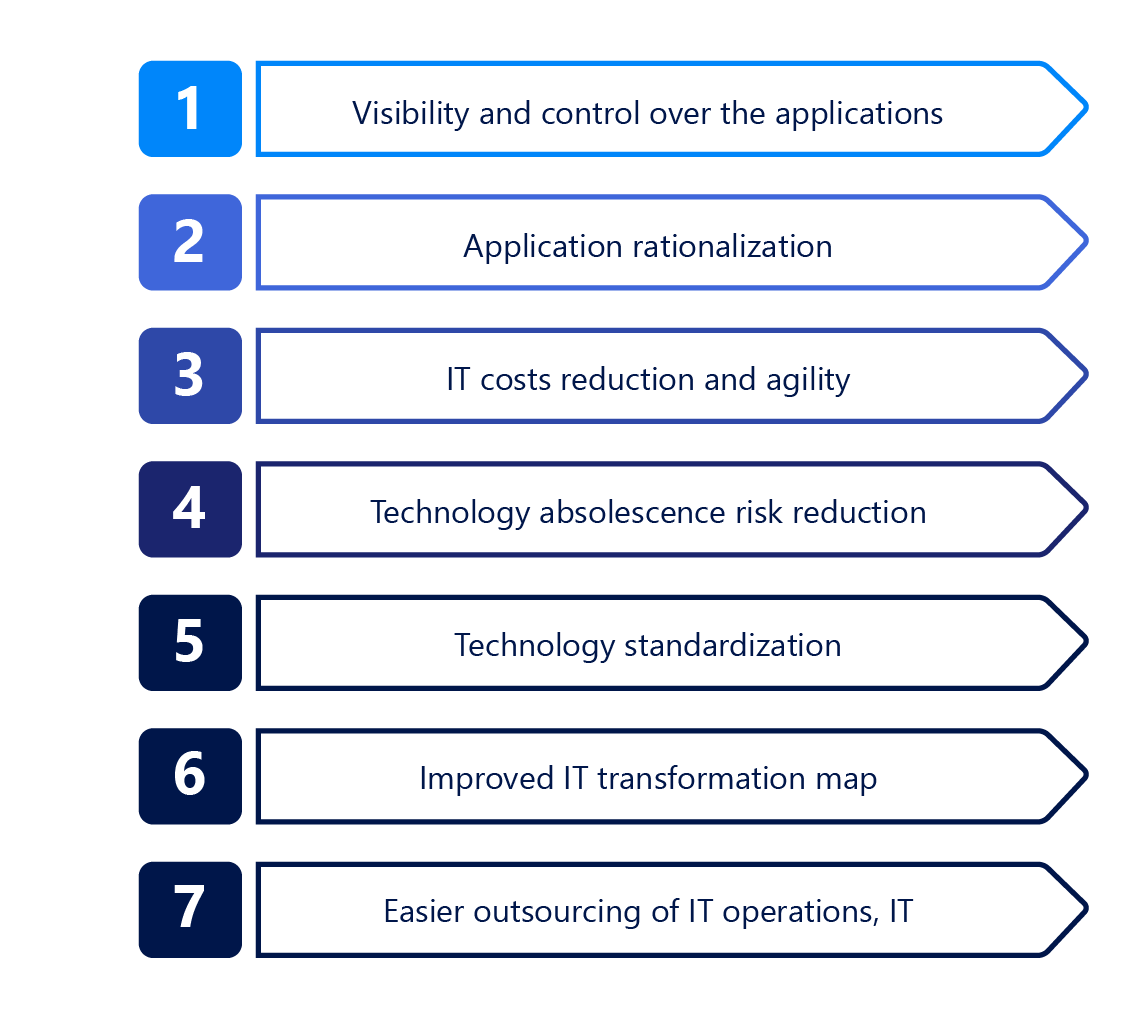

Benefits of application portfolio management (benefits of APM)

Application Portfolio Management (APM) is a great way to track all the organization's applications. It allows easy tracking of which applications are used, how frequently, and by whom.

This information can be handy for decision-makers who need to understand what is currently being used within their organization and how it affects overall productivity. Additionally, the APM system provides organizations with valuable insight into application performance and usage trends, giving them a better understanding of their technology investments' performance over time.

1. Visibility and control over the applications /IT system

Over the last few decades, many IT departments have witnessed increasing applications. This increase is often due to past mergers & acquisitions, globalization, or organic growth.

Thus, IT departments face increasing complexity and multiple redundancies. They need more visibility into their applications, and integrating new resources into their legacy systems can take time and effort.

Application Portfolio Management helps companies perform an application inventory under multiple perspectives, such as lifecycle, costs, deployments, or the business capabilities they support. IT portfolio managers can also link applications to technologies and business capabilities to understand an IT asset's impact on the business and perform what-if analysis to rationalize applications.

It is possible to call on application owners, who will update their application information to streamline the application inventory.

It can be crowdsourced to application owners, who will update their applications' information to speed up the application inventory. Overall, this inventory will provide greater visibility and a better knowledge of the IT systems, enabling IT leaders to embrace new business projects readily.

2. Application rationalization, IT cost reduction, and IT agility

Application portfolio management provides many dashboards to understand the state of the portfolio. Dashboards on application lifecycles indicate when applications will be retired or replaced by another version.

Other critical information, such as data flows between applications, clarifies the impacts of removing an application or the possibility of exchanging data with another one. However, the strength of an application portfolio management practice resides from the business perspective.

IT leaders clearly understand how applications support business capabilities, and therefore, they know which applications are critical to the business. Application Portfolio Management tools also include questionnaires that enable business users to provide satisfaction feedback on their applications.

These dashboards highlight potential inconsistencies and help better plan the IT transformation. By using these dashboards, IT managers can rationalize applications, reduce IT costs, and increase IT flexibility because they better understand their applications' business value.

3. Technology obsolescence risk reduction and standardization

IT departments often manage a vast number of software technology components that represent a threat to organizations. By limiting the variety of technology products, IT departments can perform essential economies of scale, and dev teams are better trained to use these technologies.

APM software can be connected to external libraries containing lifecycle information, including end-of-life dates, to determine technology obsolescence. Based on this information, dashboards are available that show how applications are affected by technologies' end-of-life.

Once this assessment is complete, technology portfolio managers can decide whether technologies comply with the company's standards.

By defining technology standards, technology portfolio managers help companies reduce the number of technologies – and their costs, while ensuring projects don't use rogue technologies.

4. Improved IT transformation roadmap

If application portfolio management solutions help provide the whole picture of IT systems, they also help IT managers plan their IT systems' transformation.

Based on application lifecycles and cost assumptions, IT managers can simulate future IT projects and analyze the outcome of their premises. To do so, they create a mix of initiatives based on different assumptions, such as extending or phasing out an application, and compile these initiatives into various scenarios.

Then, they can see the impact on their IT systems and compare the different scenarios.

By planning and executing the IT transformation, IT departments can allocate more resources to new business initiatives and focus on innovation.

5. Facilitates outsourcing of IT operations, IT audits, and compliance.

If an organization decides to outsource one part of its IT, it needs to make a detailed inventory of its assets and potentially eliminate irrelevant applications. Therefore, an assessment is required before deciding which applications to keep or outsource.

Another benefit is streamlining IT audits or certifications. External consulting companies or governmental organizations recommend or require companies to monitor their IT assets properly. An application portfolio management practice will help organizations better support the IT roadmap or reduce capital allocation to cover IT risk.

Learn more about:

Summary

Application Portfolio Management is an essential tool for any company. It provides an efficient and effective way to organize, manage, and update their applications. It significantly reduces complexity, simplifies IT management, and eliminates redundant applications. Furthermore, it helps organizations stay on top of the latest trends and technologies and provides a comprehensive view of the entire application landscape. Lastly, it can help improve operational efficiency by reducing costs and improving performance.