Earlier this year, we published a blog about how enterprise architects can contribute to innovation. In this blog series, we want to further explore the different roles enterprise architects can play in innovation in their organization. In general, we see an increasing need for and contribution of an architectural perspective on innovation. That’s because most large organizations have become pretty complex beasts and innovating there is not always easy. Lots of moving parts need to be coordinated but not many people have the necessary overview. This is typically where enterprise architecture can add value.

We see three key roles for architects in innovation:

In this blog series, we will explore these three roles, starting with the first.

Most established organizations have grown organically over the years, adding departments, functions and systems in a piecemeal manner without thinking about the larger impact of these additions.

Moreover, even if there was a sound and mature architecture practice involved in the evolution of the enterprise, the architectural choices of the past may no longer be adequate in present days, and especially as the enterprise is trying to move forward into the future. For example, a common architecture principle is “reuse before buy before build”: rather than creating something new, we need to reuse what we already have, because duplication of functionality is needlessly expensive, leads to data inconsistencies, et cetera. Makes sense, right? Well, maybe not always.

Applying this principle has often led to large, centralized systems that try to be everything to everyone. Those systems often started out small. Then a new requirement came in that was perhaps covered for 80% by that system but required 20% new functionality. Much better to extend the existing system a little than to buy something else, right? Let’s just switch on this extra module from the vendor, or add another table to the database… But every extension becomes gradually more difficult, since you have to consider the impact on the entire system.

So we need to do away with these monoliths. Let’s introduce service orientation and do everything with microservices: Fine-grained, light-weight, loosely-coupled functional elements with clear, standards-based interconnections. Let’s also organize our agile ‘two pizza’ teams around those services and have them innovate locally. That will make life much easier. Well, maybe not always…

All too often, microservice landscapes devolve into a similarly complicated mess of dependencies, connecting everything to everything else. Formerly, this mess may have been hidden inside the belly of your big legacy system. That we can now see it more clearly is surely progress, but again, change becomes progressively more difficult because of all the interdependencies we have introduced.

Moreover, ensuring data consistency across such a web of services is no easy task. Performance may become an issue because of the network communication between all these services. And if every team is free to choose their own technology stack (as some agile proponents want to have it), you can imagine the resulting complexity and risk for the enterprise. Finally, how do you know that what these individual teams have decided really contributes to desirable business outcomes for the enterprise as a whole?

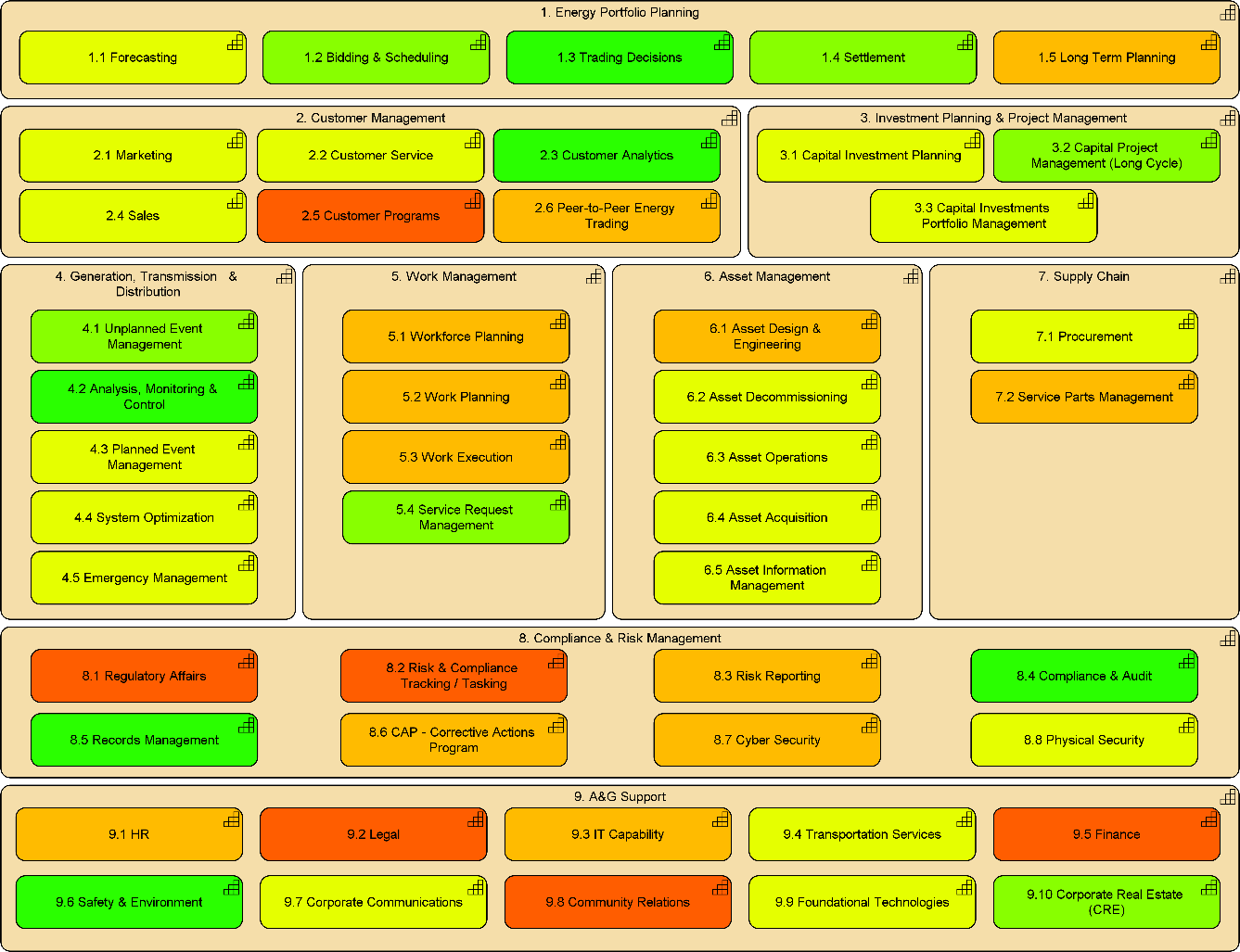

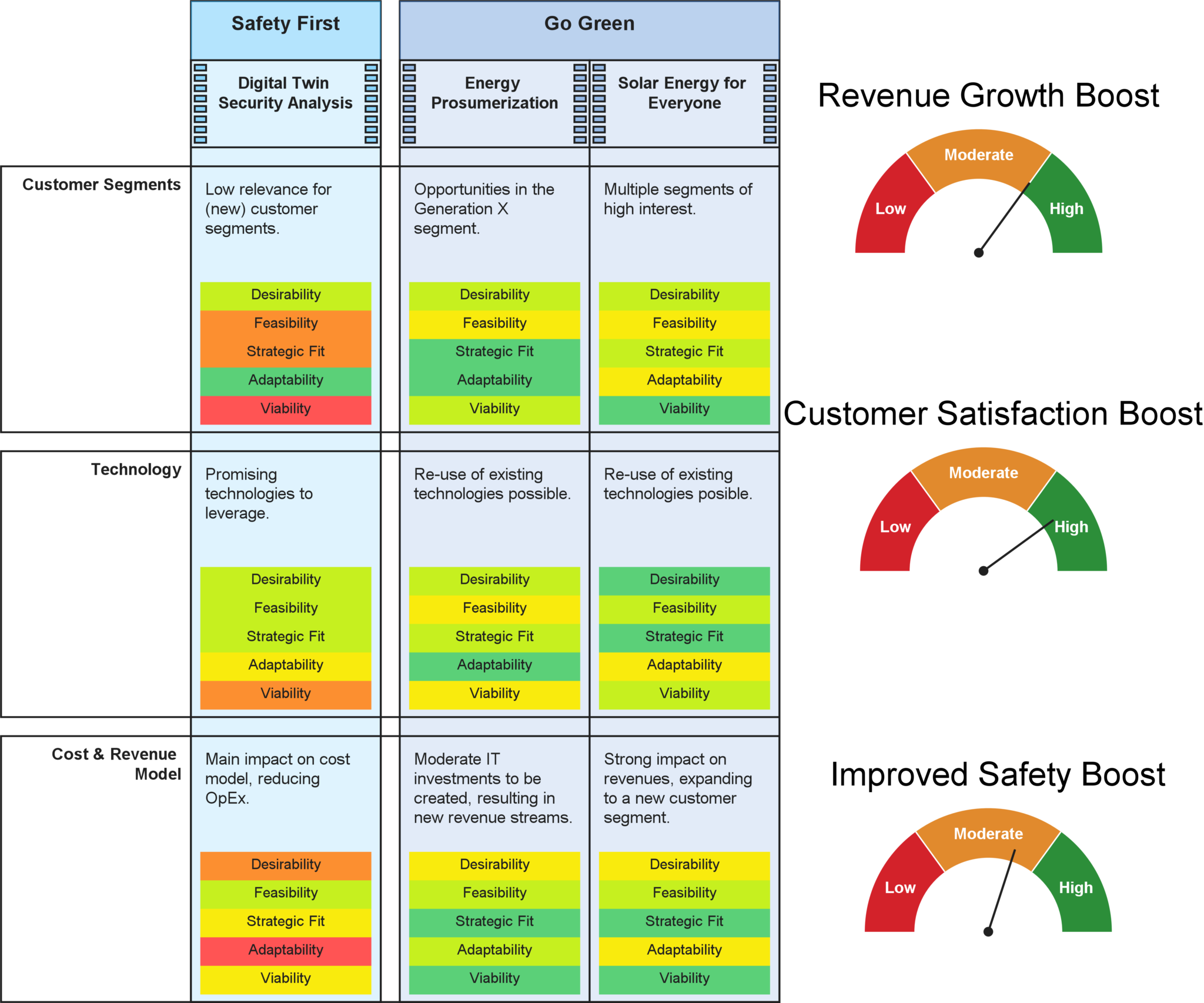

Once you consider these aspects, it becomes obvious that a solid architecture is as relevant as ever if you want to innovate and keep innovating. Classical principles around coupling and cohesion of systems still apply. From their ‘big picture’ perspective, architects can help decide where to integrate or separate the parts of your business and IT landscape. From a business level downwards, thinking about autonomous business capabilities helps you partition your architecture in independently evolving and innovating parts. Approaches like pace layering let you understand and guide the different speeds of change in the various parts of your landscape.

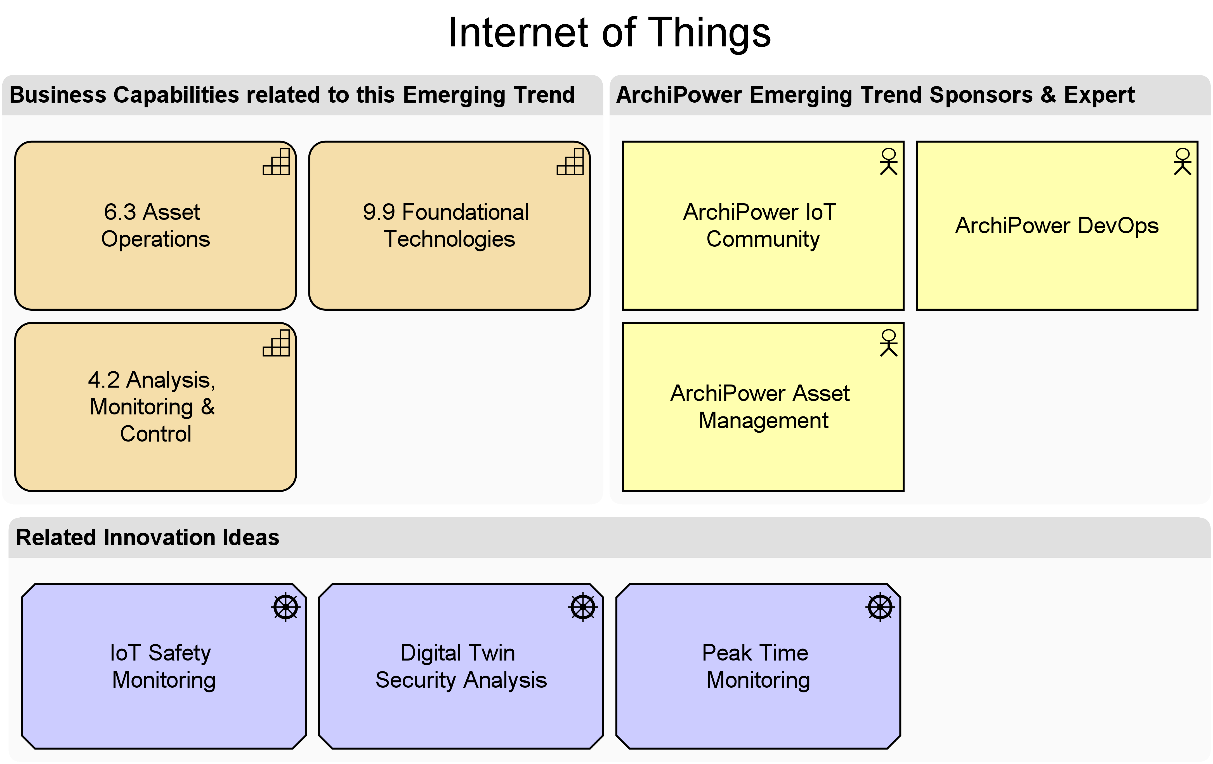

Concepts like the above not only help in reducing complexity and thereby enhancing flexibility and agility, but also in explicitly shaping space for innovation. Where could you create room for exploration and uncover potential business value, without introducing undue operational or financial risk? And there is much more in the toolbox of the architect that helps their organizations foster innovation and change. We believe that successful corporate innovation efforts are supported by smart, enterprise-wide insights and collaboration. For example:

You do need to realize, though, that the days of ‘big design up-front’ are over. Enterprise architects can no longer design a fixed target state far into the future. The world around us just changes too fast and our stakeholders’ needs change accordingly. Rather, by providing just-enough, just-in-time decisions and guidance in the form of ‘intentional architecture’, architects can help organizations stay flexible and innovative.

In the next blog post in this series, we will look at the second role of architects in innovation: coordination. Stay tuned!