To effectively assess a business capability and execute Capability-based Planning, we need to define and measure three dimensions: Strategic Importance, Capability Maturity, and Adaptability.

Simply put, the first dimension lets you prioritize those capabilities that are most important to your enterprise; the second focuses on where improvement may be needed because the current maturity is too low; and the third looks at how easy or difficult it will be to make that improvement.

The three dimensions that help us assess Business Capabilities are:

- Strategic Importance: How relevant or critical is a capability for the success of the business? This is determined in terms of its contribution to strategy execution, to the business or operating model, and to the future opportunities it provides.

- Capability Maturity: How good are we at performing this capability? This is measured in the common dimensions of people, process, information and technology.

- Adaptability: How easy or difficult would it be to change this capability? This is assessed by looking at its adaptability to the environment, to the needs of the customer, and to changes in demand.

Read more in our blog: Business Capabilities?

How do you measure the dimensions?

Most common capability assessment models use a five-level scale, probably under the influence of the CMMI maturity model for software development

- Performed

- Managed

- Defined

- Quantitatively Managed

- Optimizing

Each level has a definition, e.g. level 4 means that your capabilities or processes are measured with quantitative (e.g. statistical) techniques, with quality and performance objectives used as criteria in managing them.

A detailed assessment can evaluate various aspects of each capability, and the results can be analyzed quantitatively. This works if you want to assess a relatively small number of capabilities on domain-specific aspects. For instance, in assessing software development capabilities or processes, you can look at software defects, rework, user satisfaction, and many other metrics as input.

Doing a broad, possibly enterprise-wide, capability assessment, such as a detailed analysis, often takes too much effort. Alternatively, you could put experts in a room and ask them to rank each capability on a 1-5 scale. However, this would rely too much on personal opinion and doesn’t give these experts a foundation for their evaluation.

Our approach aims to take the middle ground. We let such a group of experts score their agreement with a number of statements about each capability on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

By limiting the number of statements per aspect and dimension, we keep the required effort to a manageable level. As an example, the Process dimension of Capability Maturity includes statements such as:

- “Each process has a clear owner who is accountable for performance.”

- “Processes are monitored with success measures that are regularly reported.”

- “Processes for the capability are fully optimized and efficient.”

For each statement, the average score of the experts is entered into the assessment model. Together, the resulting scores for a set of statements are averaged, resulting in a value for that dimension. The values for each dimension can, in turn, be averaged to calculate the overall maturity of the capability.

Capability Assessment in Bizzdesign Horizzon

In Bizzdesign Horizzon, you can use fields in data blocks to enter these assessment scores. With calculated fields, you can define an expression to compute the average across the fields for each statement and another one to calculate the overall average maturity level. You can also make this a weighted average if some dimension is more important than another.

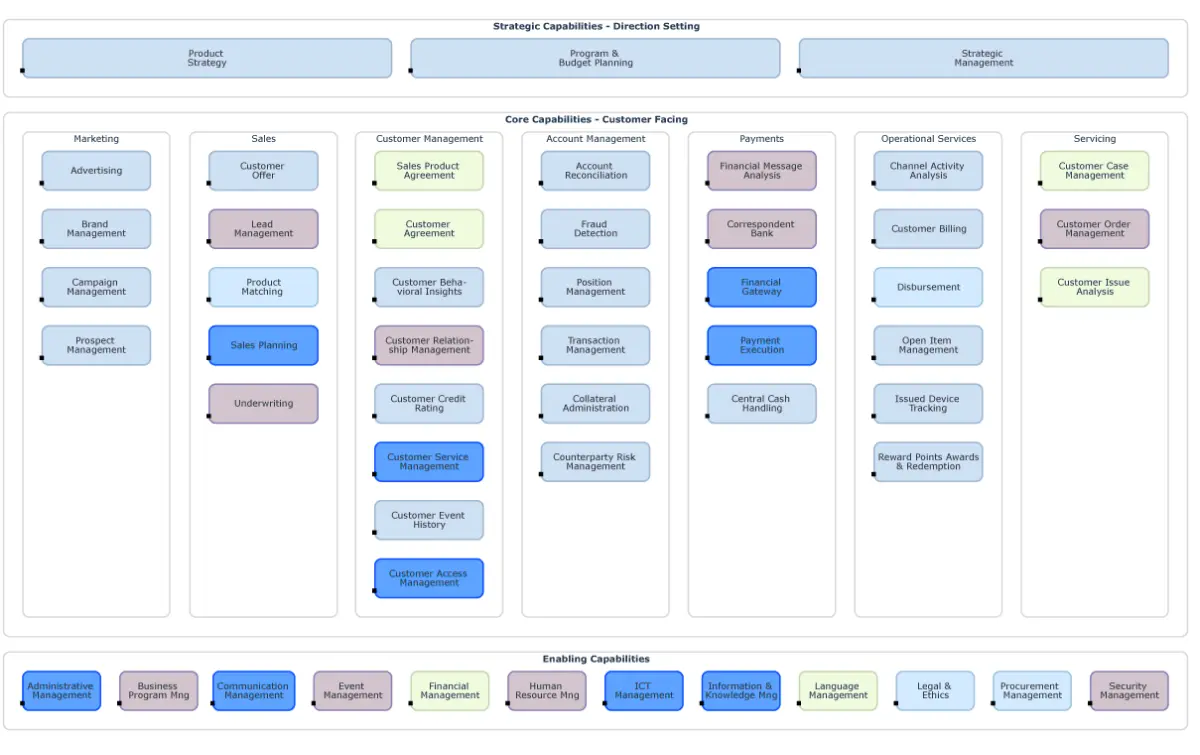

The resulting data can be shown in Bizzdesign Horizzon in several ways, such as a heat map of your Capability Map, helping you pinpoint issues such as below-par capabilities that require management attention and investment priority.

In a previous blog post on relating capabilities to your strategy and business model, we already showed an example of such a heat map, depicting the strategic importance of capabilities together with their investment levels. Similar views can, of course, be created for maturity and adaptability.

A capability heat map with IT investment levels (color) vs. strategic importance (label)

Further Analysis

Analyzing this data helps you pinpoint the pain points, where the difference between where you are and where you want to be is the greatest. Typically, high strategic importance and a low maturity business capability must be investigated first.

You want to analyze in-depth those aspects where the difference between current and desired maturity is the largest. At the same time, you may find that such a capability is not very adaptable.

You may first need to invest in improving this adaptability otherwise other changes may be too difficult, time-consuming, and costly. This is the typical worst-case scenario: a capability that’s very rigid because it heavily depends on legacy software that’s difficult to change but which is core to the operation of your enterprise, and needs urgent uplifting to keep up with competitors and customer demands.

This data can be used in many ways to support business decision-making. For instance, in Capability-based Planning you want to plan capability improvements in the most effective way, investing where it counts and when it counts.

Change initiatives could be scored by the capability improvements they provide and the concrete contribution of those improvements to strategic goals and other KPIs. Based on this, they could be compared and ranked.

One way of doing this is using the Cost of Delay of each initiative, which in turn is input for Weighted Shortest Job First prioritization of change initiatives. Assessing and improving capabilities can become more complicated in large, geographically dispersed enterprises with multiple instances (implementations) of the same capability.

Moreover, to describe the evolution of your capabilities (or rather these instances), you would typically model capability increments.