In the previous installment of this architecture models series, I wrote about organizing your model repository according to business, information and technology domains. I also explained the need to create separate current- and future-state models, and the separation between and model content and views. In this part of the series, I have a few more things to add on the topic of naming and modeling conventions, as well as advice on how to set up governance and quality assurance structure around your models.

To be able to find anything in a large-scale model, you have to know what to look for. In plain language, you’ll need to know what things are called – and how they’re labeled – in your model. This is why defining clear naming conventions is essential. Different organizations will have their own specific naming schemes, so no universal convention applies to all situations.

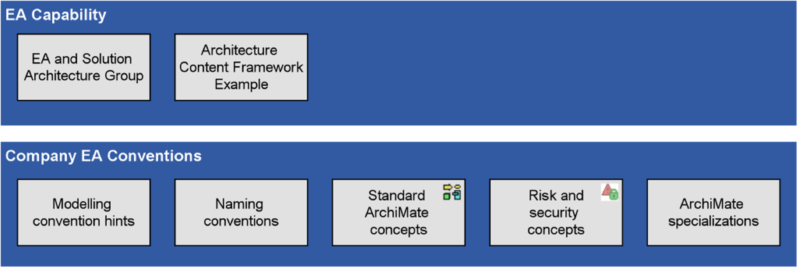

Figure 2. Overview of your EA capability, ways of working and best practices.

Nevertheless, you do need to coordinate between different departments and domains to ensure their ways of working are compatible, and to share and benefit from each other’s experiences so you can build up your own library of organization-specific best practices.

Working with such large and complex organizations, I have seen that it is often helpful to create a kind of ‘editorial board,’ composed of representative architecture and modeling experts from different areas of the organization. They can locate shared ways of working and other commonalities across your architectures (such as the modeling conventions and structuring mentioned previously), and they can coach their less experienced colleagues in applying these practices to promote high-quality models.

However, an ‘editorial board’ is not the same as your typical architecture board, which decides on the architectural content itself. Rather, this editorial board supervises the way architectures are modeled and described. These are two distinct competencies: A good architecture may be badly documented, and poor architecture may be well-documented. Make sure both are well-done.

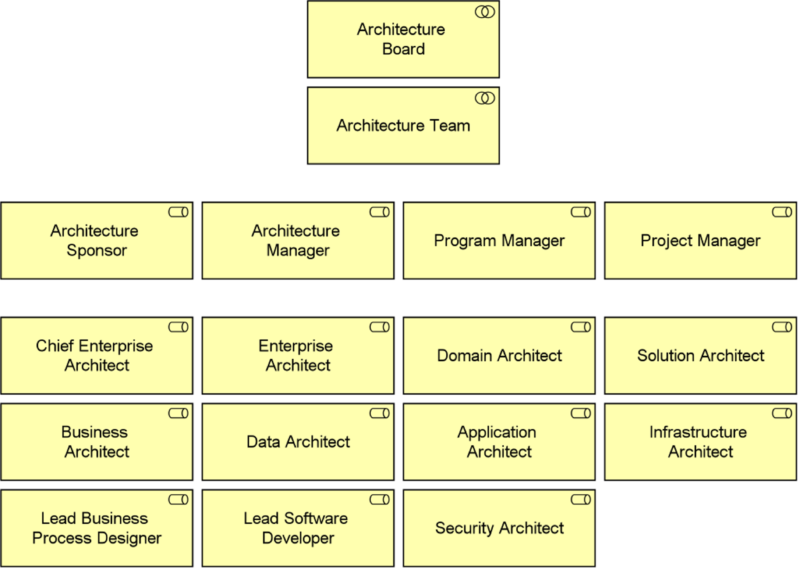

In any large-scale organization, you have to be clear about who does what and who has access to which materials. If everyone can edit anything in your architecture models, you can guess what will happen. Things may get moved or entire models may be deleted.

In general, I would not advocate hiding parts of the architecture from view (unless for specific security-related reasons). Architects should be trusted to see the work of their peers and make good use of that. However, you will likely need to limit write access to the people who have a defined role in creating or updating models. Otherwise, your models will quickly become a mess.

One way to do this is to organize the work on your future-state architectures in projects, each with their own specific models, as described above. Project teams have the right to change their project models but the results are only published to the wider architecture repository when they are sufficiently ready, as decided by a lead architect or decision maker within the organization.

Enterprise Studio’s Team Platform supports your organization’s different projects, roles and rights for designers and lead designers, and it offers user groups that can be organized as project teams. Moreover, the workflow facilities in the Horizzon portal allow you to create approval and review workflows to organize the architecture development process.

Interested to learn more about the way we support large-scale architecture endeavors? Join our webinar or book a demonstration